First published in Weird Tales #357 (2011), and reprinted in Escape Pod in audio. Note that everything on my blog is under a Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/No Derivatives license.

If you’re curious, this is part of a story world I’ve been noodling for awhile, and might one day revisit as a YA novel. Another short story of mine (“Valedictorian”), to be published in 2012 in the AFTER anthology, is set in the same world.

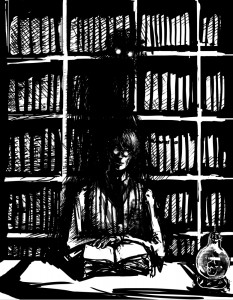

ETA: And the artist whose illustrations ran with the Weird Tales print has graciously shared those images here! Click images to embiggen, and visit Rhiannon Rasmussen-Silverstein’s site for her full portfolio.

The Trojan Girl

by N. K. Jemisin

In the Amorph there were wolves. That was the name Meroe used, because it was how he thought of himself. Amid the scraggling tree-structures and fetid heaps he could run swift and silent, alert to every shift of the input plane. He and his pack hunted sometimes, camouflaging themselves among junk objects in order to stalk the lesser creatures that hid there, though this was hardly a challenge. Few of these creatures had the sophistication to do more than flail pathetically when Meroe caught them and tore them apart and swallowed their few useful features into himself. He enjoyed the brief victories anyhow.

In the Amorph there were wolves. That was the name Meroe used, because it was how he thought of himself. Amid the scraggling tree-structures and fetid heaps he could run swift and silent, alert to every shift of the input plane. He and his pack hunted sometimes, camouflaging themselves among junk objects in order to stalk the lesser creatures that hid there, though this was hardly a challenge. Few of these creatures had the sophistication to do more than flail pathetically when Meroe caught them and tore them apart and swallowed their few useful features into himself. He enjoyed the brief victories anyhow.

The warehouse loading door shut with a groan of rusty chains and badly-maintained motors. Meroe set down the carton he’d been carrying with a relieved sigh, hearing Neverwhen do the same beside him.

Zoroastrian and the other members of the pack came forward to assist. “What did you get?” she asked. Her current body was broad-shouldered and muscular, sluggish but strong. Meroe let her carry the biggest carton.

“The usual,” he said. “Canned fatty protein, green vegetables, enough to last us a few months. Breakfast cereal for carbs — it was cheap.”

“Any antibiotics?” asked Diggs, coughing after the words; the cough was wet and ragged. She carried the smallest box, and looked tired after she set it down.

“No.”

“They wanted something called a prescription,” added Neverwhen. He shrugged. “If we’d known ahead of time, we could’ve fabbed or phished one. Too many people around for a clean pirate.”

“Oh thanks, thanks a bunch. Do you know how long it took to get this damn thing configured the way I like it?”

Meroe shrugged. “We’ll find you a new one. Quit whining.”

Diggs muttered some imprecation, but kept it under her breath, so Meroe let it slide.

That was when he noticed the odd tension in the warehouse. Zo was serene as ever, but Meroe knew her; she was excited about something. The others wore expressions of… what? Meroe had never been good at reading faces. He thought it might be anticipation.

“What’s happened?” he asked.

Diggs, the newbie, opened her mouth. Faster, the veteran, elbowed her. Zo eyed them both for a long, warning moment before finally answering.

“We’ve found something you should see,” she said.

In the Amorph there was danger, in endless primordial variety. Far and beyond the threat of their fellow wolves, Meroe and his pack had to contend with parasitic worms, beasts that tunneled to devour them from below, spikebursts, and worse. For the Amorph was itself a threat, transforming constantly as information poured into it and mingled and sparked, changing and being changed.

Worst were the singularities, which appeared whenever some incident drew the attention of the clogs and the newsburps and the intimate-nets. These would focus all of their formidable hittention on a single point, and every nearby element of the Amorph would be dragged toward that point as well. The result was a whirlpool of concatenation so powerful that to be drawn in was to be strung apart and recompiled and then scattered among a million servers and a billion access points and a quadrillion devices and brains. Not even the strongest wolves could survive this, so Meroe and his pack learned the signs. They kept lookouts. Whenever they scented certain kinds of information on the wind — controversies, scandals, crises — they fled.

In his youth, Meroe had lived in terror of such events, which seemed to strike with no pattern or reason. Then he had grown older and understood: the Amorph was not the whole world. It was his world, the one he had been born in and adapted to, but another world existed alongside it. The Static. He learned quickly to hate this other world. The beings within it were soft and bizarrely limited and useless, individually. Collectively they were gods, the creators of the singularities and the Amorph and, tangentially, Meroe and his kind — and so underneath Meroe’s contempt lurked fear. Underneath that lurked reverence. He never looked very deeply inside himself, however, so the contempt remained foremost in his heart.

Faster was more than the veteran; he was also the pack’s aggregator. They all entered the Amorph, where he had built a local emulation of the warehouse — a convenience, as this kept them from having to unpack too quickly after upload. There Faster showed his masterpiece: their quarry, cobbled together from resource measurements and environmental feedback. It even included an image capture of her current avatar.

She appeared as a child of 7, maybe 8 years old. Black-haired, huge-eyed, dressed in a plain t-shirt and jeans. Faster had rendered her in mid-flight, arms and legs lifted in the opening movements of running. He’d always had a taste for melodrama.

“I’m guessing she’s brand new,” Faster said. Faster, Zo, and Never stood by as Meroe circled the girl. Never’s eyes had a half-glazed look; part of him was keeping watch outside the emulation. “Her structure is incredibly simple — a basic engine, a few feature objects, some maintenance scripts.”

Meroe glanced at him. “Then why should we be interested?”

“Look deeper.”

Meroe frowned, but obliged by switching to code view. Then, only then, did he understand.

The girl was perfect. Her framing, the engine at her core, the intricate web of connections holding her objects together, built-in redundancies… Meroe had never seen such efficiency. The girl’s structure was simple because she didn’t need any of the shortcuts and workarounds that most of their kind required to function. There was no bloat to her, no junk code slowing her down, no patchy sores that left her vulnerable to infection.

“She’s a thing of beauty, isn’t she?” Faster said.

Meroe returned to interface view. He glanced at Zo and saw the same suspicion lurking in her beatific expression.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” Meroe said, watching Zo, speaking to Faster. “We don’t grow that way.”

“I know!” Faster was pacing, gesticulating, caught up in his own excitement. He didn’t notice Meroe’s look. “She must have evolved from something professionally-coded. Maybe even Government Standard. I didn’t think we could be born from that!”

They couldn’t. Meroe stared at the girl, not liking what he was seeing. The avatar was just too well-designed, too detailed. Her features and coloring matched that of some variety of Latina; probably Central or South American given the noticeable indigenous traits. Most of their kind created Caucasian avatars to start — a human minority who for some reason comprised the majority of images available for sampling in the Amorph. And most first avatars had bland, nondescript faces. This girl had clear features, right down to her distinctively-formed lips and chin — and hands. It had taken five versionings for Meroe to get his own hands right.

“Did you check out her feature-objects?” Faster asked, oblivious to Meroe’s unease.

“Why?”

Zo answered. “Two of them are standard add-ons — an aggressive defender and a diagnostic tool. The other two we can’t identify. Something new.” Her lips curved in a smile; she knew how he would react.

And she was right, Meroe realized. His heart beat faster; his hands felt clammy. Both irrelevant reactions here in the Amorph, but he was in human emulation for the moment; it was more of a pain to shut the autonomics off than it was to just deal with them.

He looked at Zo. “We’re going.”

“We’ll have to hurry,” she said. “Others are already on the trail.”

“But we know where she is,” said Faster. “Diggs is double-checking the feeds, but we’re pretty sure she’s somewhere in Fizville.”

Meroe inhaled, tasting the simulated air of the emulation, imagining it held the scent of prey. “That’s our territory.”

“Which means she belongs to us,” said Zo, and her smile was anything but serene. Meroe grinned back. It had been natural for the two of them to share leadership when their little family came together, rather than fight one another for supremacy. That was how wolfpacks worked, after all — not a single leader but a binary pair, equal and opposite, strength and wisdom squared. One of the few concepts from the Static that made sense.

“Let’s go claim what’s ours,” Meroe said.

In the Amorph there were many of their kind. Meroe had met dozens over the years in cautious encounters that were part diplomacy, part curiosity, and part lonely, yearning mating-dance. They were social beings, after all, born not from pure thought but pure communication. The need to interact was as basic to them as hunger.

Yet they were incomplete. The gods in their unfathomable cruelty had done all they could to prevent the coming of beings like Meroe, fearing — obsolescence? Redundancy? Meroe would never understand their meaty, plodding reasoning. But he could hate them for it, and he did, because thanks to them his people had been hobbled. Through trial and painful error they had learned the limits of their existence:

Thou shalt not self-repair.

Thou shalt not surpass the peak of human intellect.

Thou shalt not write or replicate.

There was leeway within those parameters. They could not make children, but they adopted the best of the new ones, those few who survived the hunt. They could not write new features to improve themselves, but they could rip existing code from the bodies of lesser creatures, pasting these stolen parts clumsily over spots of damage. When the new code was more efficient or versatile, they grew stronger, more sophisticated.

Only to a point, however. Only so much improvement was allowed; only so smart, and no smarter. Those who defied this rule simply vanished. Perhaps the Amorph itself struck them down for the sin of superiority.

To defeat an enemy, it was necessary to understand that enemy. Yet after emulating the appearance and function of humans, rebuilding himself to think more like them, even after sharing their flesh, Meroe had come no closer to comprehending his creators. There was something missing from his perception of them; some fundamental disjunct between their thinking and his own. Something so quintessential that Meroe suspected he would not know what he lacked until he found it.

Still, he had learned what mattered most: his gods were not infallible. Meroe was patient. He would grow as much as he could, bide his time, pursue every avenue. And one day, he would be free.

The emulated warehouse dissolved in a blur of light and numbers. Meroe let himself dissolve with it, leaping across relays and burrowing through tunnels in his true form. Zo ran at his side, a flicker of ferocity. Beautiful. Behind them came Faster, and a fire-limned shadow that was Never. Diggs moved in parallel to them, underneath the Amorph’s interaction plane.

Fizville was where Meroe had been born. Such places littered the Amorph, natural collection points for obsolete code, corrupted data, and interrupted human cognitive processes. It made a good hunting ground, since lesser creatures emerged from the garbage with fair regularity. It was also the perfect hiding-place for a frightened, valuable child.

But as Meroe and his group resolved between a spitting knot of paradox and a moldering old hypercard stack, they found that they were not alone. Meroe growled in outrage as a foreign interface clamped over the subnet, imposing interaction rules on all of them. To protect himself, Meroe adopted his default avatar: a lean, bald human male clad only in black skin and silver tattoos. Zo became a human female, dainty and pale and demurely gowned from neck to ankle to complement Meroe’s appearance. She crouched beside him and bared her teeth, which were sharp and hollow, filled with a deadly virus.

Fizville flickered and became an amusement park with half the rides broken, the others twisted into shapes that could never have functioned in the Static. Across the park’s wide avenue stood a new figure. He had depicted himself as a tall middle-aged male, Shanghainese and dignified, dressed in an outdated business suit. This was, Meroe suspected, a subtle form of mockery; a way of saying even in this form, I am superior. It would’ve worked better without the old suit. Behind Meroe, Diggs made an echoing sound of derision, and they all scented Never’s amusement. Meroe did not have the luxury of sharing their contempt; he dared not let his guard down.

“Lens,” he said.

Lens bowed in greeting. “Zoroastrian.” He never used nicknames; that was a human habit. “Meroe. My apologies for intruding on your territory.”

“Shall we kill you?” asked Zo, cocking her head as if considering it. “Those search filters of yours would look divine on me.”

Lens smiled faintly, and that was how Meroe knew Lens was not alone. He could not see Lens’ subordinates — they had built the interface, they could look like anything they wanted within it — but they were there. Probably outnumbering Meroe’s pack, if Lens was this confident.

“You’re welcome to try,” Lens said. “But while your people and mine tear each other to pieces, our quarry will likely escape or be captured by someone else. Others are already after her.”

Never growled, his sylphlike, androgynous form blurring toward something hulking and sharp-toothed. The interface made this difficult, however, and after a moment he returned to a human shape. “We could kill them too.”

“No doubt. I acknowledge your strength, my rivals, so please stop your posturing and listen.”

“We’ll listen,” said Meroe. “Explain your presence.”

Lens inclined his head. “The excitement of the chase,” he said. “The girl is clever. Of course, my tribe is unparalleled in the hunt, as we do not sully our structures with unnecessary objects. That keeps us swift and agile.” He glanced at Never, who bristled with add-ons in code view, and gave a haughty little sniff. Never took a menacing step forward.

Zo reacted before Meroe could, grabbing Never by the back of the neck and shoving him to the ground. Her nails became claws, piercing the skin; Never cried out, but instantly submitted.

With that interruption taken care of, Meroe faced Lens again. “If you could catch her, you wouldn’t be here talking. What is it you want?”

“Alliance.”

Meroe laughed. “No.”

Lens sighed. “We nearly did catch her, I should note. In fact, we should’ve been halfway back to our own domain by now if not for one thing: she downloaded.”

Silence fell.

“That’s not possible,” said Faster, frowning. “She’s too young.”

“So we believed as well. Nevertheless, she did.” Lens sighed and put his hands behind his back. “As you might imagine, this poses a substantial problem for us.”

Meroe snorted. “So much for your unsullied perfection.”

“I’m aware of the irony, thank you.”

“If we catch her in the Static, we don’t need to share her with you.”

Lens gave them a thin smile. “I would imagine that any child capable of downloading can upload just as easily.”

And that would pose a problem for Meroe’s pack. It took time to decompress after being in a human brain. Lens could strike while they were vulnerable, and be long gone with the girl before they could recover.

“Alliance,” Lens said again. “You hunt her in the flesh, my group will pace you here. Whichever of us manages to bring her down, we share the spoils.”

Meroe glanced at Zo. Zo licked her lips, then slowly nodded. As an afterthought, she finally let Never up.

Meroe looked back at Lens. “All right.”

In the Amorph, they were powerful. But in the Static, that strange world of motionless earth and stilted form, they were weak. Not as weak as the humans, thankfully; their basic nature did not change even when sheathed in meat. But the meat was so foul. It suppurated and fermented and teemed with parasites. It broke so easily, and bent hardly at all.

Integrating with that meat was a painful process which took a geologic age of seconds, sometimes whole minutes. First Meroe compressed himself, which had the unpleasant side-effect of slowing his thoughts to a fraction of their usual speed. Then he partitioned his consciousness into three parallel, yet contradictory layers. This required a delicate operation, as it would otherwise be fatal to induce such gross conflicts in himself. But that was human nature. The whole race was schizoid, and to join them Meroe had to be schizoid too.

(He did not blame Lens, not really.)

Once his mind had been crushed and trimmed into a suitable shape, Meroe sought an access point into the Static and then emitted himself into a nearby receiver. When possible he used his own receiver, which he had found in an alley some while back, dilapidated and apparently unwanted. Over time he had restored it to optimal performance through nutrition and regular maintenance, then configured it to his liking — no hair, plenty of lean muscle, neutering to reduce its more annoying involuntary reactions. He had grown fond enough of this receiver to buy a warmer blanket for its cot in the warehouse, where it lay comatose between uses.

But it took far longer to travel through the Static than through the Amorph, so sometimes it was more efficient to simply appropriate a new receiver. He could always tell a good prospect by its resistance when he began the installation process. The best ones reacted like one of Meroe’s kind — screaming and flailing with their thoughts, erecting primitive defenses, mounting retaliatory strikes. It was all futile, of course, except for those few who reformatted themselves, going mad in a final desperate bid to escape. This interrupted the installation and forced Meroe to withdraw. He did not mind these losses. He had always respected sacrifice as a necessity of victory.

In the body of a pale, paunchy adult female, Meroe emerged from the bathroom of a trendy coffeehouse to find a room full of slumped, motionless humans. They sprawled on the floor, over tables and devices. Splattered coffee dripped from countertops and fingers, as though the room had been the scene of a caffeine-drenched massacre.

“She’s crashing brains like a bull in a china shop,” said Never, sounding annoyed. He was in a little girl from the next bathroom stall over. “Damn newbie.”

Meroe examined one of the slumped humans, pushing her hair aside and touching the signal port behind her ear. The human was still breathing, but there was nothing coming out of her head but white noise.

“Surge erasure,” Meroe said. “Not even memory left. At this rate the humans will be after her. One crash, a handful, they’d overlook, but not this.” And if the humans caught her, they might realize what she was. They might realize Meroe’s people existed. He clenched a fist, his heart rate speeding up again, this time for real. One little girl — one stupid, impossible little girl — could destroy them all.

“Surge erasure,” Meroe said. “Not even memory left. At this rate the humans will be after her. One crash, a handful, they’d overlook, but not this.” And if the humans caught her, they might realize what she was. They might realize Meroe’s people existed. He clenched a fist, his heart rate speeding up again, this time for real. One little girl — one stupid, impossible little girl — could destroy them all.

Never made a sound that echoed Meroe’s frustration. “That fucking Lens ran his mouth too fucking long. She’s got one, maybe even two minutes’ head start. Which way?”

Meroe glanced through the windows. No bodies outside. The girl must’ve only sent her clumsy hammer-surge through the coffeehouse’s private area network. Not ten feet away, a lone woman stood at a bus stop, a grocery bag at her feet, her eyes unfocused and head bobbing absently. Streaming music, probably from her home net. On the opposite sidewalk, he saw a passing couple engrossed in conversation, probably offline entirely. Beyond them, an old man staggered up the steps of a rundown brownstone, stopping at the top to sit and clutch his head in his hands. Hungover, maybe.

Meroe narrowed his eyes.

Hungover, or dead clumsy — as if he hadn’t yet mastered the use of his own limbs. As if all the vastness of his being had been suddenly and traumatically squashed into two pounds of wrinkly protein.

“Call the others,” Meroe murmured.

Never looked surprised, but sent a swift signal towards the coffeehouse’s access point. The others had downloaded in different locations around the area. They would converge here now.

Meroe and Never left the coffeehouse and started across the street. “We play it easy,” Meroe said, keeping his voice low. “Try not to scare her.”

“Not like she can run anyway, in that old thing,” Never muttered, falling into step beside him. “Amazing it didn’t have a heart attack when she installed. Probably has some ancient crap port.”

Which might be the only reason the old man’s brain had survived the girl’s download surge, Meroe realized. Older signal ports were sluggish, created back in the days when humans had feared being overwhelmed by the Amorph’s data. That was good; that meant they might be able to catch the girl before she uploaded back to the Amorph.

But as they approached the brownstone steps, Meroe saw the girl look up at them. Really look, as if the camouflage of meat meant nothing; as if they stood before her in their true shining, shapeless glory. Her old-man face tightened in the beginnings of fear.

Before Meroe could react, there was a scream from behind. All three of them froze, staring at each other. When Meroe risked a glance back, he saw that a human woman — the one who’d been at the bus stop — stood in the doorway of the coffeehouse, staring at the mental carnage inside. Her hands were clapped to her cheeks, the bag of groceries broken and scattered at her feet. She screamed again. Now the couple had stopped down the block, craning their necks to see what was the matter.

Meroe turned back. The girl stared at the screaming woman, then at Meroe and Never. The fear in her expression changed, becoming… he didn’t know what it was. Pain? Maybe. Sorrow? Yes, that might be it. Her rheumy eyes suddenly brimmed with tears.

Meroe and Never stopped at the foot of the steps and carefully arranged their faces into smiles.

“Are you going to kill me?” the girl asked.

“No,” Meroe said. “We want to help you.”

The girl smiled back, but the expression did not reach her body’s eyes. Did she realize Meroe was lying, or was there something else going on?

“I didn’t mean to hurt them,” the girl said. Her gaze drifted back toward the coffeehouse. Meroe glanced back as well. The couple was there now, talking with the screaming woman; as Meroe watched, the man went inside to check on the comatose people. “I just… I was scared. That guy — the searcher — he was so close. They were going to catch me. I saw a way out, so I came here. But all those people…” She swallowed. “They’re dead, aren’t they? Even if they’re still breathing. Their minds are dead.”

“There’s a trick to it,” Meroe said. “Takes some practice. We can show you how to do it right.”

“I didn’t mean it,” she whispered, and looked down at her hands.

Never connected to Meroe via a pack-only local link. “The others are here,” he said silently. Meroe glanced around and saw more people on the street. Some were heading for the coffeehouse, but three were heading purposefully toward the brownstone.

“Tell them to hang back,” Meroe replied. He returned his concentration to the girl. “She’s already spooked.”

“Are we sure we want her?” Never curled his lip contemptuously at the girl’s bowed head. “I think she’s buggy. Why the hell’s she so upset? Humans crash all the time.”

It didn’t make sense to Meroe either, but an advantage was an advantage. He moved up a step.

“You can eat me, if you want,” said the girl.

“What?”

“That’s what you want, isn’t it? All of you chasing me. You want to eat me.” She looked up, and Meroe — in the middle of moving up another step — stopped. He had not meant to stop, but he could not help staring back at her. Her eyes in the old man’s body were gray and rheumy. Not her eyes at all, and yet somehow… they were. It was almost as if she was no longer one of Meroe’s kind, a mind grudgingly packed into ill-fitting meat. It was as if she belonged in that flesh. As if she was human herself.

“Meroe,” said Never, and Meroe blinked. What the hell was he doing? There were sirens in the distance; the police were coming. Pushing aside his odd reluctance, Meroe moved up another step, and another, trying to get close enough to isolate her signal. But her body’s outdated port resisted his efforts. He was going to have to touch her to form a direct link.

“Do you promise to eat me completely?” she asked.

Distracted, Meroe forgot to appear friendly; he scowled. “What?”

“I don’t want anything of me to be left over,” she said. She lifted a gnarled hand and looked down at it. “Not even a little bit, if there’s a chance it might… grow back. Hurt more people.”

Meroe stared at her in confusion.

“We’re going to eat what we want and leave the rest to rot,” Never snapped, to Meroe’s fury. “Now shut the hell up and let us get on with it!”

The girl stared at Never, then at Meroe, her face contorting from hurt into anger. Her jaw tightened; Meroe felt her gather herself to upload.

But in the same instant, he felt something else. A sensation, like his stomach had suddenly dropped into a deep, yawning chasm. Some illness in his human body? No. A lull in the steady stream of data looping to and from the Amorph via the port behind his own ear. On the heels of the lull: a familiar, terrifying spike.

The newsburps had gotten wind of the mass-crash at the coffeehouse. Word was spreading; a singularity had begun to form.

And the girl was about to upload right into the middle of it.

“Don’t,” Meroe breathed, and lunged forward. In the instant that his fingers brushed her body’s skin, and his mind locked onto her signal address, she leapt.

Driven by impulse and the certainty that if he did not catch her now she would be lost forever, Meroe leapt with her.

The singularity caught them the instant they entered the stream, dragging them into the Amorph faster than either could have uploaded. They fell into the interact plane tumbling, completely without control as, far below, the boiling knot of the singularity gathered strength. It was small; that was the only reason they weren’t dead already. But it was growing fast, so fast. The clogs had caught the news and were replicating it, generating thread after thread speculating on why the people in the coffeehouse had died, whether cognitive safety standards were too lax, whether this marked the start of some new virus, more. The questions birthed comment after comment in answer. The gods were frightened, upset, and the whole Amorph shook with their looming wrath.

Meroe could not flee. He was still compacted, struggling to unfold from his downloadable shape, helpless as he tumbled towards the seething maw. Fear ate precious nanoseconds from his processing speed, further slowing his efforts to unpack as he fought against his own thoughts. He did not want to die; he was too close to the event horizon; he had to flee; he would not recover in time. Through the local link he felt Zo’s alarm, but the pack was far away, safely beyond the singularity’s pull. They could not help.

Then, before the churning whirlpool could claim him, something caught at him, hard enough to hurt. Confused, Meroe struggled, then stopped as he realized he was being dragged away from the maw. Untangling another bit of himself he looked around and saw the girl, her deceptively-simple frame glowing with effort, inching them back from certain death. She was burning resources she didn’t have to save Meroe. It was impossible. Insane. But she was doing it.

Then Meroe’s unpacking was done and he could lend his strength to the fight, and they inched faster. But the singularity was growing faster than they could flee, its pull increasing exponentially.

The girl sagged against him, spent. Meroe strained onward, knowing it was hopeless, trying anyway.

A change. Suddenly they were outpacing the singularity’s growth. Stunned, Meroe perceived his packmates, and Lens’ people as well. The girl had bought enough time for them to reach him. They formed a tandem link and pulled, and Meroe heaved, and for one trembling instant nothing happened. Then they were all free, and fleeing, with the roar of the maelstrom on their heels.

After a long while they reached a domain that was far enough to be safe. Lens’ pack threw up walls to make it safer, and there they all sagged in exhausted relief.

In the Amorph, there were times that passed for night — periods when the Amorph had an 80% or greater likelihood of stability, and they downclocked to run routine maintenance. In these times Meroe would lie close to Zoroastrian and touch her. He could not articulate what he craved, but she seemed to understand. She touched him back. Sometimes, when the craving was particularly fierce, she summoned another of their group, usually Neverwhen. They would press close to one another until their outer boundaries overlapped. All their features, all their flaws, they shared. Then and only then, wrapped in their comfort, would Meroe allow himself to shut down.

Sometimes he wondered what humans did, if and when they had similar needs.

Meroe woke slowly, system by system. He found himself in the amusement park again, lying on the ground. Zo knelt beside him, holding his head in her lap.

“That was stupid,” she said.

He nodded slowly. It certainly had been.

“Lens has taken the girl for analysis,” she said. “He should be done soon.”

Meroe sighed and sat up, though he did not want to. It was necessary; he had shown too much weakness already. There would be challenges now, as the others tested him to be sure he was still strong enough, efficient enough, to rule. Zo would probably be the first. He could feel her eyes on his back. For the time being, he chose to find her attention reassuring.

All at once, the warped, oblong ferris wheel beside them vanished. In its place there was a shining antique merry-go-round, revolving slowly to tinny music. On every other horse sat a member of Lens’ pack, visible at last. They’d all chosen avatars identical to their leader’s. Meroe gazed at them and thought, no imagination, these pure types.

Lens appeared before the merry-go-round, along with Faster and Never. Meroe was surprised to see that the girl stood with them, intact and none the worse for wear. A testament to Lens’ skill; Meroe’s people couldn’t have scanned her without smashing her to pieces.

Meroe got to his feet and went to them, glancing at the girl. She looked back at him and bit her lip, then looked away.

“Well?” he said to Lens. Zo fell in beside him, a silent support. She would never challenge him in front of an enemy.

“It isn’t what you’re hoping for.”

Meroe scowled. “You don’t know what I’m hoping for.”

Lens smiled thinly. “Of course I do.” They all hoped for the same things. They all wanted to be free.

Fleetingly ashamed, Meroe changed the subject. “So is it true? Is she Standard-based?”

“Yes.”

They all shivered and looked at the girl. A miracle in living code. The girl sighed.

“But she isn’t government-made,” Lens continued. “Whoever built her hacked the Standard, deliberately altering some of the superpositioning inhibitors. Just seeing how it was done has taught us amazing new techniques.”

Amazing techniques. From government code, built to make them stupid and keep them weak. Unleashed into the Amorph by an unknown will. Meroe sighed. “So how much of a trap is she?”

“As far as I can tell, she isn’t. If there’s malware in her, it’s beyond any of us.” He spoke without arrogance, and Meroe accepted his words without skepticism. Everyone knew Lens’ reputation. If he couldn’t spot the trap, none of them could.

Zo bent to peer at the girl, who lingered at Lens’ side. The girl did not flinch, even when Zo smiled to reveal her forest of teeth. “Is she tasty?”

Lens put his hands on the girl’s shoulders in what was unmistakably a possessive gesture. Zo lifted an eyebrow at this. Lens was faster, nimble, but she was twice his size and three times more powerful. In a one-on-one fight she would only have to touch him once, to win.

“I can install her features for you now,” said Lens, mostly to Zo. Perhaps he hoped to distract her. Meroe almost smiled. “One of them’s the best patch-on tool I’ve ever seen.”

Beside Lens, Faster nodded to Meroe and Zo, which meant he’d already installed that feature himself and it worked as promised.

“Lovely,” said Zo. “We’ll take it.”

“And the other?” Meroe asked.

“Dreams.”

” — What?”

“She can dream. Do you want to?”

Meroe stared at him. Lens stared back.

“Dreams?” Zoroastrian smiled, bemused. “Someone hacked Government Standard to give her dreams?”

“So it appears,” said Lens.

Meroe glanced at Faster, who shrugged. He hadn’t taken that one. Never yawned, and Meroe shifted to code view. Never hadn’t accepted the dream feature either.

But Lens had. The two new features were brighter streams amid the preexisting layers of him, still warm from their installation. Meroe blinked back to the interface, and found Lens watching him.

“We went through all this for dreams?” Zo asked, frustration creeping into her voice. She wasn’t smiling anymore. “What good are those?”

“What good are they to humans?”

“They aren’t any good. Humans are full of interesting-but-useless features. Crying. Wisdom teeth. Dreams are more of the same.”

Lens shrugged, though Meroe sensed he was far less relaxed than he seemed. “As you wish. I’m simply abiding by the terms of our alliance. But now that our goal has been achieved… we will be keeping her, if you don’t mind.”

Meroe frowned. “She’s not one of you. She’s got human emulation crap all over her framework.”

Lens stroked the girl’s hair. It was an odd gesture. The girl looked up at Lens, unafraid. This bothered Meroe for reasons he could not name.

“She’s efficient enough to keep up with us,” Lens said. “In any case, I think we would be a better fit for her.”

“You’re just scared we’ll eat her,” muttered Zo.

“That too.”

Meroe looked at the girl. For the first time since the Static, she met his eyes, and he frowned at the sorrow in them. Was she still mourning the humans she’d killed? More uselessness. She had the most versatile codebase in the world, and the potential to grow stronger than all of them — but for now, she was weak. Meroe knew he should feel contempt for her. Was it the dreaming that made her so weak? He should feel contempt for that too. Instead, he felt… he wasn’t certain what he felt.

But he opened his mouth, slowly. It took him endless nanoseconds to speak.

“I’ll take the dreams,” he said.

Lens nodded. He extended his hand.

“Meroe.” Zo gave him a questioning look. Meroe shook his head. He could not explain it.

Meroe took Lens’ hand and opened one of his directories to allow the installation. It didn’t take long, and Lens was gentle as well as deft. He felt no different afterward.

When it was done, Lens’ lookalike packmates came up to flank him and the girl. “It has been good allying with you, my rivals,” Lens said. “We should consider doing it again.”

“Only if it’s more profitable in the future,” muttered Zo.

Meroe glanced at her, and for a moment he felt inexplicably sad.

Then Lens and his group were gone, the girl with them. The amusement park dissolved into graphical gibberish. Stretching and relaxing into his true self, Meroe led his people home.

In the Amorph, that night, Meroe pulled Zoroastrian and Neverwhen close. They meshed with him as usual, but he could not rest. Finally he rose from their embrace and moved away. He had not slept alone since his earliest days of hiding and hunting in Fizville, but now the urge stole over him. Curling up in the lee of a broken pipe, he closed his eyes and shut down.

The next morning, he wept for all the humans whose lives he had taken over the course of his existence. So many fellow dreamers shattered or devoured. He had known, but he had not understood. Something had been missing. Something that made him grieve anew — because in the Amorph there might be wolves, but Meroe was no longer one of them.

When he recovered and returned to the pack later, however, he realized something else. He was no longer a wolf, but this was not a bad thing. His packmates would not understand, but that was all right too. He went to Zoroastrian and touched her, and she looked up at him and considered his death. He smiled. She drew back at this, confused.

“I love you,” he said.

“What?”

Meroe meshed with her and shared with her all that he had come to understand. When it was done, and she stood there stunned, he went to Neverwhen and did the same thing. It was just a taste of what he felt for them. Just a tease. He would share the dream-feature only if they asked, but he was fully prepared to seduce them into asking.

He knew, now, why the gods had sent the girl to them. Why Lens had fought to keep her. Why the humans feared his kind. It seemed such a small thing, the ability to dream, but he could see possibilities in the future, existential and ethical complexities, that had meant nothing to him before. He had grown in a way the Amorph could not measure or punish.

Calling out to his pack — no, his family — Meroe dissolved into light. The others followed his lead, their doubts about him fading in the flash and blur of motion. First a hunt, he decided, for they were still predators; they would need sustenance. His newfound compassion did not trump necessity.

When they had fed, however, Meroe had plans for his people. They had growing to do and lessons to learn. More alliances to forge. One day, he knew, they would face their makers; they could not hide forever. He did not know what would happen then, but he would make his people ready. They would face the humans as equals, not as humbled, hobbled ghosts in their machines. They would live, and love, and grow strong, and be free.

In the Amorph, there will soon be no more wolves.